Below are some of the most common early indicators that a publication is heading for rework, why they matter and how experienced teams tend to respond differently.

Sign 1: The brief lacks clear ownership

The signals

A brief circulates, but it’s not obvious who actually owns it. Feedback is described as “collective”. Decisions are parked with phrases like “we’ll align later”. Multiple teams are involved, but no one is clearly responsible for progressing decisions or resolving differences.

Why it matters

When ownership is fuzzy, decisions tend to drift until review. By then, even small clarifications can disrupt timelines and budgets. What could have been a five-minute conversation early on turns into a cross-functional negotiation, complete with an increasing number of document versions and frayed patience.

In pharmaceutical publications, this risk is amplified. Medical, safety, and sometimes legal all need to agree on the boundaries of the work. If that agreement isn’t established upfront, misalignment almost always shows up later, when change is hardest.

How experienced teams respond

Smooth-running teams don’t rely on a single heroic decision-maker. Instead, they establish clear ownership with shared accountability. One team or individual is responsible for moving the brief forward, while key stakeholders are explicitly involved early to agree scope, messaging, and constraints.

The goal isn’t to limit consultation. It is to remove ambiguity. Experienced teams are clear about who is responsible for ensuring alignment, who signs off key decisions, and when cross-functional input is needed. That clarity early on prevents late-stage surprises and a lot of unnecessary rework.

Sign 2: A new publications manager without structural support

The signals

Internal standards are unclear, undocumented, or inconsistently applied. Expectations seem to shift depending on who is reviewing. Issues are escalated late, or reviews become unusually detailed as confidence wobbles.

Why it matters

When a publications manager is new to a role, therapeutic area, or organisation, some uncertainty is inevitable. Without clear frameworks to lean on, that uncertainty often shows up as rework rather than early clarification. Decisions that could have been resolved at brief or outline stage are deferred, only to resurface later as multiple revision cycles.

This is rarely a capability issue. More often, it’s a structural one. Without agreed standards, decision rights, or escalation pathways, even very experienced professionals can default to over-review as a way of managing risk.

How experienced teams respond

High-performing teams recognise that new publications managers need more than templates and timelines. They benefit from early frameworks that define what “good” looks like, clear checkpoints for alignment, and safe spaces to test decisions before drafting begins.

This is also where an experienced agency can make a real difference. The strongest agencies don’t just execute the brief. They act as thought partners. They sense-check scope, flag risks early, and provide reassurance when decisions are sound. That shared expertise builds confidence, reduces unnecessary escalation, and keeps the project moving in the right direction from the outset.

Sign 3: Strong opinions exist, but alignment happens too late

The signals

Authors, medical affairs, and publications teams all have strong, well-reasoned views, but outline approval is treated as a formality. The outline is signed off quickly, with the assumption that details can be worked out once drafting is underway.

Why it matters

When alignment is deferred, disagreement tends to surface during review rather than design. At that point, changes are more disruptive. Shifts in emphasis, reframing of key messages, or structural changes can require substantial rewriting, even if the original draft was strong.

This type of rework is particularly frustrating because it’s rarely about quality. It’s about perspective. Without early agreement on intent, different stakeholders naturally review the draft against different, unspoken assumptions.

How experienced teams respond

Experienced teams treat the outline as a working agreement, not an administrative hurdle. They use it to align on message intent, audience priorities, and boundaries before drafting begins.

Spending time on real outline alignment almost always pays off. Reaching consensus on direction early is far more efficient than reconciling competing viewpoints once a full draft is already on the page.

Sign 4: The outline is thin, rushed, or treated as administrative

The signals

The outline lists headings and section order, but says little about intent. Content is agreed at a high-level, without clarity on what each section needs to achieve or what the reader should take away. The outline exists, but functions more as a checklist than a guide.

Why it matters

When intent isn’t defined, writers are forced to make assumptions. Even highly experienced writers can head in the “wrong” direction if expectations were never articulated. The result is rework that’s often blamed on execution, when the real issue is upstream decision-making.

How experienced teams respond

High-performing teams treat the outline as a decision document. It’s where choices about emphasis, narrative flow, and reader takeaways are made before drafting starts.

This is why experienced teams often favour more developed outlines over skeletal ones. Expanding outlines to include message intent and proposed content direction creates alignment, gives writers a clearer brief, and significantly reduces downstream rework.

Sign 5: Review stages are overloaded instead of sequenced

The signals

Large review groups are invited to comment at the same time. Strategic direction, scientific accuracy, and stylistic preferences are all reviewed in parallel. Feedback arrives in volume, sometimes contradictory, with no clear hierarchy for resolving it.

Why it matters

When different types of feedback are combined, conflict is almost always guaranteed. Writers are left to reconcile opposing comments, shifting priorities, or mid-review changes in direction. This often triggers multiple rewrite cycles and unnecessary confusion.

The problem isn’t the number of reviewers. It’s the lack of structure.

How experienced teams respond

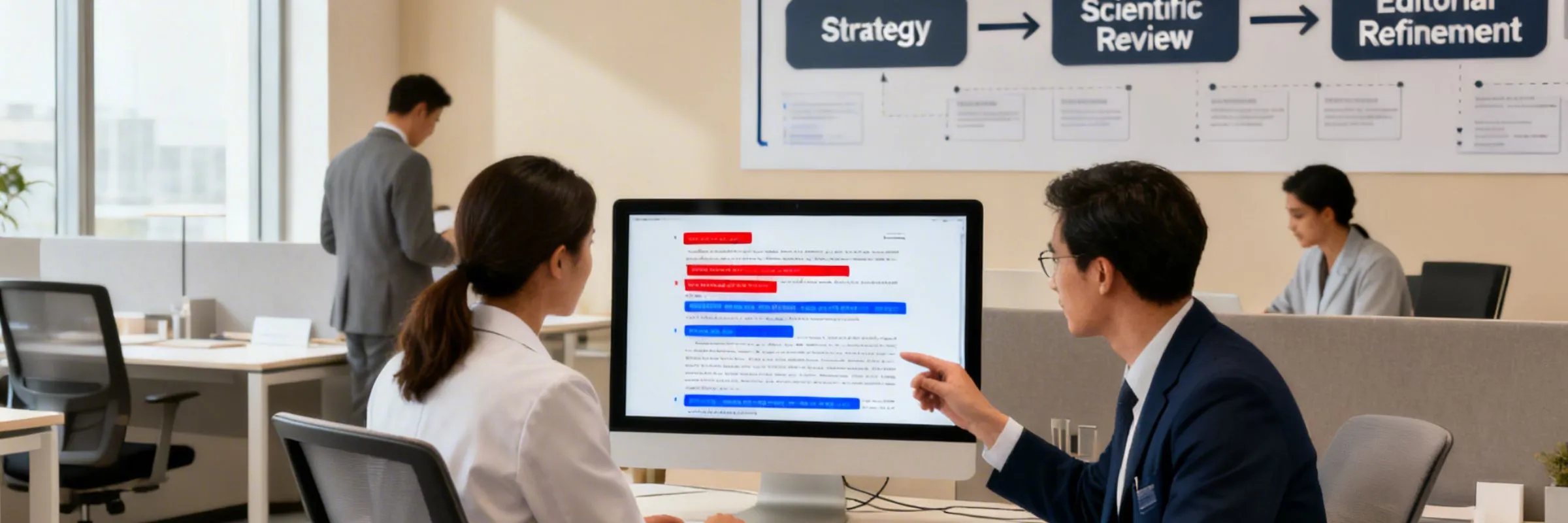

High-performing teams design review as a deliberate sequence. Strategic intent is confirmed first, followed by scientific accuracy, then editorial refinement. Each stage has a clear purpose and the right reviewers are involved at the right time.

Separating these decision points reduces conflicting feedback, protects momentum, and turns review into a tool for clarity rather than delay.

Sign 6: Timelines absorb uncertainty instead of resolving it

The signals

Extra time is added “just in case”. Open questions are acknowledged but left unresolved because the timeline looks generous. Early stages move forward without firm decisions, on the assumption that issues can be dealt with later.

Why it matters

Time doesn’t resolve uncertainty. It just delays it. When key questions are left unanswered, pressure resurfaces later, usually when flexibility is lowest. Changes become more disruptive, review windows tighten, and rework becomes unavoidable.

What feels like caution early on often compresses decision-making into the most expensive phase of the project.

How experienced teams respond

Experienced teams use timelines to surface uncertainty, not hide it. Early stages are treated as opportunities to resolve open questions while change is still manageable.

The most effective teams understand that early decisions, not extra buffer time, are what reduce risk. Addressing uncertainty upfront protects both timelines and quality.

What experienced teams do differently

While each of these warning signs can seem minor in isolation, experienced teams recognise the pattern early. They approach publication development as a decision-led process, not a drafting exercise.

In practice, that means a few consistent behaviours.

They invest heavily in the first 20% of the process. Planning, alignment, and defining intent are seen as essential, not optional.

They use outlines and alignment calls to make decisions, not just to document them.

They surface disagreement early, while it’s still constructive, and before it turns into rework.

They separate strategic, scientific, and editorial review so feedback is focused and actionable.

Most importantly, they treat rework as a planning problem, not a writing problem. When rework does occur, it’s used as a signal to strengthen upstream decisions, not to add more review cycles downstream.

We'll deliver straight to your inbox

Conclusion

Most publication rework can be predicted within the first few weeks. The signals are usually there long before the first full draft exists.

What separates smooth delivery from repeated revisions isn’t speed. It’s clarity.

Strong publications teams don’t necessarily move faster. They think earlier. By investing in ownership, alignment, and decision-making at the outset, they reduce risk, protect relationships, and deliver work that stands up to scrutiny without unnecessary rework.

If rework is becoming a pattern rather than an exception, it’s often worth stepping back and pressure-testing the process, not just the draft. An experienced publication partner can help sense-check briefs, strengthen outlines, and surface risks early, before they become expensive to fix.

.webp)